In mid-January, Eike König of Hort Berlin taught a week-long practicum workshop culminating in an exhibition in CalArts’ L-Shaped Gallery.

Workshop participants were challenged to work off the screen and compose a series of prints by hand. Students explored a range of printmaking methods, including printing with simple, geometric foam shapes to make experimental letterforms and illustrative compositions, as well as an number of abstract compositions using their own found materials. The L-Shaped Gallery was filled with over 70 playful, colorful prints in the week following the workshop.

During his visit, Eike kindly sat down with Christina Huang and myself to speak a bit about his design practice, collaboration, and the state of design education today.

Christina Huang: To begin, what is your favorite typeface, or a typeface you feel is underrated?

Eike König: Oh wow. I don’t know. It always really depends on the context. I mean, there are bad typefaces for sure, but it’s the context that really makes the typeface shine or makes it completely wrong. I don’t have any favorite color, favorite typeface, favorite food, or favorite designer. I just have one favorite person, and that’s the woman to whom I’m engaged. I know that’s very minimalistic, but I can fall in love with a lot of things when I develop an interest in them. So even when a typeface is not in my comfort zone, I can have a relationship with and probably try to understand it and maybe also use it. For me it always feels like having a “I like that and I don’t like that” cuts off so many things that I could maybe like if I was not taught not to. I find out that I learn the most if I’m not so dogmatic about my own work; because you can always say “this is shit and this is good.” But it’s only shit because it’s part of your biography and you accepted that as your own truth, but there is no truth and there are eight billion truths. Each person has their own view on things. I’m not the one arrogant person saying “I think this is good and this is bad.” So I can’t answer your question [laughs].

CH: To me, that seems like it sort of embodies the attitude or philosophy of graphic design in general. Where you’re analyzing a particular challenge and trying to draw from everything around you and create your own point of view for a solution.

EK: There’s never one solution, there are always a million solutions. I would never say “this is the best” or “there must be better solutions.” It’s this arrogance I’m talking about, this idea of a genius is a romantic idea, it doesn’t exist. It’s just hard work. It’s understanding problems, being open to asking the right questions. But it’s also way more complicated than that. When I was younger, a lot of professors told me “your work should look like Eike König.” I was like, “what is that?” If I always put myself stylistically first on a project then then who am I supporting? It’s good that I’m always a part of my work, but I think that each problem needs its own solution. That is why I like to work with people as a team. Hort is not Eike König. Each member of the team defines how Hort looks now, and the group influences the direction we go. It is not hierarchical, it is flat. You can learn so much from the people you work with. If it’s always about you, it ends quickly and gets boring.

CH: Speaking of the studio dynamic at Hort, what is your experience collaborating with other designers? What is your perfect recipe for a good collaboration?

EK: I’m a big fan of open source. [I don’t like] this whole idea of copyright; this idea of being the author of the world, working by yourself. Working by yourself is very safe because you know how to handle your projects and your comfort zone. But it’s very hard to push yourself out of that comfort zone.

So, when I started my business, I was working alone. And then I figured out that I can do a lot of things, but I can’t do everything (although I always wanted to!). But when I was 30 I had a bit of a breakdown because I was very successful and had achieved many of my goals, but I didn’t know what should be the next step, so I said “why not work with other people?” Opening myself up and stepping back from my ego and saying “it’s not just me, it’s me with others.” By not treating these people as assistants, and by making the design process open so everyone can join in and deliver ideas, and creating a space where there are no good or bad ideas, we are able to talk them out and come up with solutions as a team, which are always much stronger than anything I can come up with by myself.

There’s a big trust in these people, which is the foundation, so I don’t need to be in charge. If I didn’t trust them, they would not be happy, and their work would always feel controlled, so I thought, “why should I create a classic company instead of a collective in which everyone is responsible for themselves?” We each define the system. If they have small projects, they can do those themselves. I think it became a blueprint for how other small studios work. At the time when I started Hort there was no role model for that. I was working as an intern at a Swiss advertising agency, and no one really asked me anything, my opinion was not relevant, they treated me like a student. This is why I created this non-hierarchical space: an environment in which I need to feel safe and supported. I couldn’t find it, so I created it [laughs]. That’s what everyone can do!

Ella Gold: You seem to really like your colleagues. How do you find the people you work with?

EK: They have to do an internship. Everyone who has ever worked with me has done an internship. I don’t know when I started the program, but we are changing it at the moment because our collective system doesn’t really work with a traditional internship program. We want to do something more of a residency, where someone applies with a project and we help them with that project.

Interns have always been important to me, especially having been an intern and feeling like “what can I really learn if someone is not really listening to me?” If I’m exchangeable, what’s the point. In the beginning we had only one intern. Now we have two interns for six months each that are completely different in thinking and design, and they have to sit and work together and become friends. Usually they would have never met, because they are so different and we tend to socialize with those who are more like us. After 6 months you know a lot about a person and you can see how well someone integrates into the team. I know that sounds like a bad word, but it’s more like “how can both sides get the best out of a relationship?” We all, as creative people, have an ego, but when you work on a team you have to be open to there being better ideas than yours. This is something not everyone can do. So, It’s kind of a natural way of figuring out, “do you like me and do I like you?” Then you stay or not. But these people are not exchangeable, I have a strong relationship with them, they help me a lot, they are part of my biography, I learn so much from them.

CH: When we spoke earlier, you mentioned something about how in the past, ideas of right and wrong came from professors. As an educator yourself, I’m curious about your thoughts on the current state of design education.

EK: I organize my class like I organize my studio. It’s like a scaled up version of Hort. They are a very diverse group: painters, sculptors, graphic designers, musicians. It’s very research based and much more interesting than if everyone is doing posters or something like that because the questions are different. A painter has different questions than a designer. You can learn a lot from other disciplines.

I try to organize my class in a way to show they are responsible for themselves. I can just trigger them, show them first how important it is and how much responsibility is involved with being a designer. If you design something for a weapon company, you aren’t just getting paid, you are working with weapons. So this responsibility is not just something they get from school, that’s my job I think. I’m also taking care of their social life. I like to foster community and have my students be in a group. Even though they may be competitors eventually, they will learn so much from each other while they are in school. When you’re a competitor you don’t share things and I want them to share ideas. Trying to understand What are their skills, where are they weak, what are their interests? How can I support them from strengthening and changing those weakness into positivity. How can they create opinions and from that an attitude.

I don’t want my students to make work like mine. You can’t do that. I try as hard as possible to not be influential and have a little clone of myself. Some teachers really need that for their ego, but if you are a successful designer with a signature, and you have 20 students, your students won’t ever be as successful as you because they will always be connected to you. You’re doing something wrong then. You can share your process and your tricks, but those shouldn’t be the dogma.

There’s still this idea of “I know a lot and you don’t know anything.” But my students know so much I don’t know! If you have only one way of communication you can’t learn anything. You guys keep me young! The things you talk about are not necessarily my world or my problems. I can learn so much from you guys. The discussions I have with my students. This is why I’m doing this. It’s not the money. I could make more money with my business. Teaching is not because of money, you do this because you like to keep the discussion going, not getting stuck in your good old times when you were successful.

EG: Do you have some strategies you like to come back to if you get stuck?

EK: Yeah, then I go do something different. I go for a walk. I don’t force it. The good thing about working with a team is there’s always someone with an idea. If you create a network of people you work with, you’re never alone with being stuck. I don’t spend time if I’m stuck. I don’t work on something when I’m stuck. I put it aside and sleep, and your brain is regulating and you have a solution or you don’t. You shouldn’t climb that wall in front of you. It’s like surfing. If the swell is going out, don’t try to go in, but go sideways where there’s a channel. I don’t spend too much energy in climbing walls that are too high. I try it a little bit, but then I figure out that maybe tomorrow it will shrink, and oh! It’s not a wall anymore. These creative blocks come up in different situations, and most are connected to your biography; it’s often something that triggers you to be afraid. Sometimes it’s different, it’s located somewhere else.

EG: I’m interested in how your personal work serves your commercial work, and how you frame your practice and make time for the different pieces.

EK: I organized Hort so I don’t need to be there really. I’m there at the beginning [of a project] if I’m part of it, but I don’t need to finish things. I’m still the firefighter, because I’m the one that’s talking to the clients mostly when there’s a problem. But I have a great studio manager who takes care of most things. If they need me I’m there, but if not, I am out. Because of that I can go off and teach.

My artistic practice came out of this residency I did at Villa Massimo [in 2013]. At first it was just a project for myself, but the more I got into the project the bigger it got. At first it was three months, and then all of a sudden it’s been five years. I open a door and another door opens and another and there’s always then the next room. Of course it’s related to my design practice and vice versa. I’m still working with typography, usually poster format, and language. Language is the tool to argue about your work or getting feedback. Such a strong tool to sell your work. And most students don’t know that. If you make good work and a client doesn’t like it, it’s not just a shitty client, you need to be able to argue for your work. Or maybe your design is just shitty. Your work cannot speak for itself.

So, it’s about language for me. I love to read, it’s a very powerful tool by which you can start a war and you can fall in love. It’s so powerful. For sure in my culture, written language is a strong part of it. The German language has such a large vocabulary and can be used so precisely. Language is also an organism that is changing, and I too am an organism that is changing. I feel very connected to it as a tool that defines a culture. Language is a code that people don’t understand or do understand.

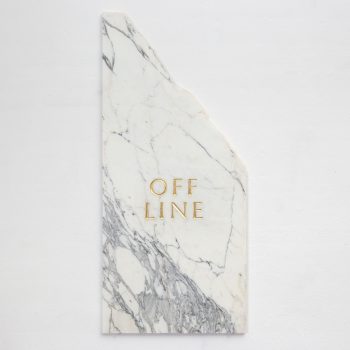

A lot of new language coming from digitalization and connection through the internet is English. “Offline” — it means nothing in German. These are the words of our time, they describe the society. What does offline mean? If you put it in the graveyard and use an old technique, a stone cutter and a hundred thousand year old stone, it becomes absurd, it has a kind of humor in it that’s a reflection of our time. You look in the mirror and think “what the fuck is offline?” These are the possibilities we have with language.

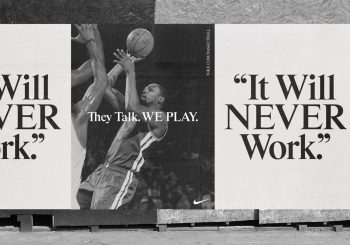

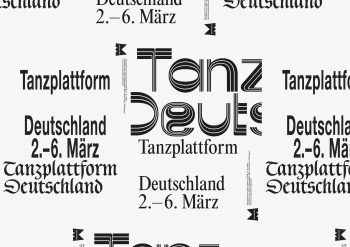

Hort emerged from the Frankfurt techno scene in 1994, originally founded by Eike König as “Eikes grafischer Hort”. The studio moved to Berlin in 2007 and has been growing as a group ever since. Hort does art direction, branding, creative consultancy, editorial design, graphic design, illustration, lectures and workshops. Hort works with institutions such as Arte, Bauhaus Dessau, Bergen Assembly, Mousonturm, Frankfurter Positionen and Tanzplattform Deutschland, as well as brands like Adobe, IBM, Microsoft, Nike, The New York Times and Universal Music. People working at Hort are Anne Büttner, Eike König, Elizabeth Legate, Tim Rehm, Tim Schmitt, Tim Sürken and Alan Woo, together with other freelancers and interns.