In September, CalArts launched a UI/UX Specialization on the Coursera platform. As part of the Open Learning initiative, Jennifer Hutton and Lina Christie worked with graphic design faculty Roman Jaster and Michael Worthington to create the four-course program focusing on design in the digital sphere.

Initially, Coursera approached CalArts about developing a course in user experience design after the success of the school’s previous Graphic Design Specialization. Coursera had noticed that many users were searching for UX courses, so Jaster and Worthington worked to create courses tailored to those needs while Worthington devised a complementary curriculum in UI to keep the Specialization within a graphic design context.

Hutton’s role was to oversee course development, which included working with Jaster and Worthington on shaping their curriculum for an online platform and ensuring learning goals were met, in addition to managing production of lecture video content, visual assets, and marketing. Concurrently, Christie worked to draft and build assignments in the course through planning and discussion with the instructors. Other help came from students and alumni, some of whom went through a test run of the course and created project examples.

The Specialization is targeted to the many Coursera students who are already out of school, working full-time, and looking for a way to boost their skills and experience or prepare for a career switch. Hutton says that shorter courses focused on applied skills—like UI/UX design—that students could follow on their own time seemed to work best.

We spoke further with Jaster about both the creation of the course and the broader role of Coursera and MOOCs in design education.

Nadia Haile: How did you and Michael [Worthington] split up the courses?

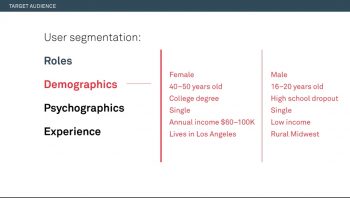

Roman Jaster: Michael decided to do the beginning courses, and I decided to do the more advanced courses— it’s a course sequence, it’s a Specialization—and ideally students will take each course sequentially. They don’t have to—but there’s a logic to the way we structured it. The thing that I really added to the mix is an emphasis on strategy. So questions like, “Who’s the user? What am I even trying to solve in the first place?” Michael’s courses are a bit more about the visual side of things.

NH: Did you base your curriculum on something existing?

RJ: Yes. I’ve been teaching this class since 2012 and the foundation is in a book called The Elements of User Experience, by Jesse James Garrett. It is kind of a standard text for the UX field, and I’ve taken that as a basis and transformed it to make it my own over the last few years. It’s basically separating the process in distinct phases, like a strategy phase and an outline of scope phase, and then a sitemap phase, until you get to the visual design at the end. It’s also based on my experience as a UX designer.

NH: What do you hope people get out of the course? What do you hope they take away?

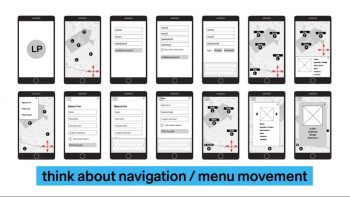

RJ: For my two classes, I hope people get a solid structure out of it: a process. There’s a potential to get a project like “design a website” and the first thing you do is you sit down and design the homepage and say “Hey, something like this?” My process that I’m teaching is: wait, no, step back for a second and ask more fundamental questions. What are you trying to achieve? What’s the problem? What are the goals that the client has? What are the goals that your users have? Who are your users in the first place? Once you establish that, what content will satisfy your goals that you set out? Then, once you have the content, how do you structure that content to make sense? What’s the navigation? Then you look at a low level, or low-fidelity, design of each page without thinking about, “What’s the background color? What’s the typeface?” That fun visual stuff comes later. It’s this structured, guided process instead of jumping right away to the visuals. Let’s do a little bit of work beforehand to ask more fundamental questions so that, when you get to the visual design, the structure of the site, and the content, is solid.

NH: Do you think that that’s rooted in sort of a design thinking model, or do you think of it separate from that?

RJ: I guess, like the whole question of understanding the problem first.

NH: Right, and I think there’s a lot of discussion in that process about investigating the user, or the customer, or whoever’s at the other end of it first.

RJ: Yeah, and this course is for people who are kind of hearing about this for the first time. So I’m teaching this course in a very systematic manner where one step follows the next. That’s not necessarily how reality happens because reality is way more messy. When you do it in practice, things are a bit more circular. There are these terms “agile” versus “waterfall,” where waterfall process has this step-by-step-by-step process and you end up with the final product in the end. An Agile process does things more quickly, so you get to a testable end result in front of users more quickly. Then you test that, learn from it, and go through the process again. I guess I’m teaching the class introducing each phase slowly and distinctly, but the next step for students would be to look at a project going through these steps quickly to get to a testable wireframe or prototype and test assumptions not in the end, but throughout. I think that’s a very design thinking kind of focus.

NH: Michael wrote a post when the CalArts Coursera first started in 2016 about MOOCs, and he frames MOOCs as an introduction to a field and not a replacement for a school education. Do you think your idea of MOOCs lines up with that or do you think things have changed since even two years ago?

RJ: Yeah, it’s funny thinking about it. I’ve told people there’s this online course I teach and one of the first questions can be, “Oh, does that mean you’re irrelevant as a teacher now because you put all your ‘knowledge’ in this video and now people can watch that?” Michael had a really nice way of framing these online courses when he first recruited me. In a way, he told me, it’s like writing a book. I think that metaphor is apt, especially since there are little to no interactions with the students in a Coursera class. You post the course and it lives on its own, and you hope for the best just like when you write a book. The author isn’t there to explain anything afterwards. People read the book and they deal with the content on their own, and that’s how I see these courses working as well. That’s why it doesn’t replace in-person instruction, where there’s much more of a conversation. I give you an assignment, you come back with it, we crit it with me as the expert giving advice on what happened—I think that’s a very different educational model than reading a book or watching an online course. Granted, these MOOCs have interaction between students. There’s technology that makes certain things a little bit more flexible, but people didn’t say because there were textbooks before that a college education is irrelevant. But for certain students—if you’re a designer or you want to try it out and get your foot in the door—it’s a great first step. But I don’t think it replaces a traditional education.

NH: What do you think are the advantages of taking Coursera courses versus self-teaching through a textbook?

RJ: A Coursera course is not as passive as a book. Some books might include exercises, but there’s no community. It’s just you. Coursera includes peer reviews and grading by peers. This increases the stakes and adds accountability. It’s so easy to read a book and forget most of it, but Coursera really forces you to engage with the material, and that makes for a deeper learning experience. In the end of my course, students also have a substantial portfolio piece. That’s the hope: that people have something to show.

NH: Were there any challenges in making the Coursera courses? What was your process in creating it like?

RJ: It’s not an overstatement to say it was very difficult. We worked on this for almost a year and there was no student feedback. When you teach a regular class, you go to the first class, you have a syllabus, but you don’t have the class planned completely. You look at what the vibe is, what students show up, what the needs are, and you adjust it along the way. For this you don’t get feedback until it’s all done. You work on it and work on it, and you record lectures, and you do that for a year and you don’t get this kind of reward—the reward of a student saying, “Oh, I understand something now”—or you don’t get to see the first part of a project where people are excited about their ideas. [As for] the processes, I feel like it was very much like writing a book, so what Michael said in the beginning rang really true. I wrote out many of my lectures and then I recorded them, but in the end, it was also rewarding. When you’re writing, as anyone who’s writing knows, sometimes you don’t really know what you think until you start writing, so it clarified a lot of things in my mind.

NH: Do you think that will then be put back into your class here?

RJ: Definitely. Last semester, I was halfway through my Coursera course, and I taught a very similar process in my live class here, and there was a nice feedback between that. It already felt like things had clarified in my mind, and I was able to teach it better. That’s for sure very rewarding.

NH: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

RJ: What was certainly helpful for me was the support I got through CalArts, especially from Jen Hutton and Lina Christie. I was talking about not getting feedback from students, but I did get feedback from Jen and Lina. I almost feel like I wouldn’t have made it through the process if they hadn’t been so helpful and enthusiastic. CalArts is lucky to have them on their team.

Roman Jaster is a graphic designer working in Los Angeles. He is the co-founder of the design studio Yay Brigade. His work is focused on web design and development, as well as book design, often for cultural organizations and artists. Roman graduated from the CalArts graphic design program in 2007 where he now teaches web design classes.

View the UI/UX Specialization on Coursera or watch the introduction video.